Dan Allen of And Scarlet Leonine is probably one of the coolest people I know. He's a talented musician and an all around nice guy, too. He's got the true spirit of DIY rock and never fails to deliver music that is at once delicate and bruising. After reading the interview and listening to the tracks, make your way over to And Scarlet Leonine's Bandcamp site and support a true artist!

You’ve played in a few bands in your time. How have your tastes and interests evolved since your early days as a musician and how has this affected the type of music you write and play?

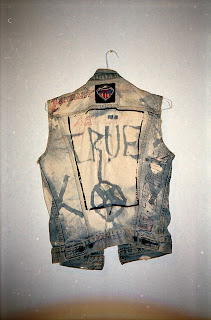

I started out playing punk music as a teenager but even then I was into a lot of different types of music. I've always been pretty open to different styles. I think over time I've just become more open to stuff. A good song is a good song; it can come in any form.

Who are some of your main musical influences and what about their music do you find inspiring?

It’s hard to name anything that is a direct influence because I listen to stuff all over the map. There are definitely certain aesthetics and ideas that influence elements of what I'm doing, but apart from that I'm not sure. Little bits and pieces seep in from all over the place. I sort of think of it like this: If you only listen to 2 or 3 bands then you're going to make music that sounds like those 2 or 3 bands, but if you listen to thousands of bands then you (hopefully) won't really sound like anything in particular.

One of your more recent projects has been an E.P. of incredible Ace of Base covers. Where did this idea come from? And why Ace of Base?

I did “The Sign” when I was working on the last record (The Night) – it’s a good pop song and it was sort of a joke, just sort of fun to do a version of it . After that I thought “Don't Turn Around” would work well, too, and for that one I definitely put a lot more thought and time into it. Ace of Base is an interesting band. It’s total pop music but there is something a little dark there under the surface.

And Scarlet Leonine - Don't Turn Around (Ace of Base cover)

How have computers and the internet affected your approach to writing, recording, and releasing music?

It hasn't really affected the writing and recording side of things. I've always been into the DIY mindset of recording, so before I had a computer setup to do multitrack recording, I was doing stuff on 4-track. Now it’s just a lot easier. I guess for releasing stuff the internet helps to get the stuff out there to people who may never have had a chance to hear it.

How do you see the album, as an art form, changing as a result of MP3s, filesharing, and the iPod? Is it more positive or negative to you?

It’s hard to say if it’s positive or negative, it’s just different. You can't fight technology so you have to sort of work with what happening at the moment. In some ways it seems like album culture is dead or dying and things have moved back to the world of “singles” rather than full records, but there are still a lot of people who appreciate a whole record. Who knows; it still sort of feels like things are in a state of limbo in between the way the music world of the past was and where it’s all going to end up.

When you write a song, what comes first – music or lyrics?

It’s sort of weird. I've never sat down and planned to write a song - that doesn't really work for me. They really just happen when the moment is right. I think every song I've ever come up with started with a guitar and some type of vocal melody. The words seem to form after a bit of time as the idea comes more into focus. I've never had a bunch of lyrics that I try to write a song around or the music of a song that I try and come up with vocals for.

Describe your process from initial writing to finished recording. How do your songs change throughout that process?

So after I have a song that is just a guitar and vocals, I'll usually have some ideas as to what else I'm going to add. A lot does happen in the recording process, experimenting with different sounds and ideas until it gets to a point that I think makes sense.

What instruments and equipment do you use to record and produce your work?

Mostly just the traditional stuff. 2 electric guitars (a hollowbody and a solidbody), 2 acoustic (a 12-string and a 6-string), 1 bass, 15 vintage keyboards, a few effects pedals. I just picked up an old Traynor reverb unit, which I'm pretty happy about.

Sister Psych with And Scarlet Leonine - Attitude (Misfits cover)

Do you see any connection between music and other art forms? In what ways do other, non-musical art or artists influence your work?

Absolutely, the whole “And Scarlet Leonine” project is very much influenced by silent era films.

One thing I really enjoy about your music is that you use the languages of different genres and combine them to create something fresh and engaging. There’s a familiarity to the music, but it doesn’t sound stale in any way; your music sounds very current and contemporary while also paying homage to the past. Has the development of your aesthetic been a planned, “I want it to sound like this” sort of thing, or has it been a more organic process?

Thanks. It definitely wasn't planned. I think it sort of goes back to what I said about listening to a lot of different stuff. If you're drawing from a large pool of influences it sort of comes out that way. The aesthetics of “The Night” were planned, in a way. I wanted that record to sound as if it could have been recorded in the late 70's or early 80's, so apart from the computer at the end of the line, every single element used to create that record was pre 1985 technology. I also wanted it to be raw, so it’s really noisy - most of the stuff was only one or two takes. I really didn't want to over-think it, [so I] left all the mistakes in there. The mistakes usually end up being my favourite parts because they are very natural and unplanned and generally not something I would ever think to do, but after listening back a few times, they seem to just work.

Tell me a bit about the Capohedz. The Capos really got shit going in a town that is, at best, reluctant to accept new ideas or creative efforts. How did it all start and where is it all going?

It started as sort of an artist collective as a way to try and get things done, help each other out and document what was going on at the time. We never really believed in the attitude of “Why isn't anyone doing anything to help the bands out around here?” which seemed to be pretty common in Cambridge. We thought more along the lines of, “If you want something done, then get to work and do it yourself.” We put on a lot of shows, put out a lot of records and zines, etc. It was good, but things changed when the Capohedz core members moved on to different phases in our lives. So the Capohedz aren't really active anymore.

Where can people get ahold of your music?

You can listen to “The Night” in high quality at http://andscarletleonine.bandcamp.com/ and download it for a couple bucks if you have Paypal. The Ace of Base stuff is on Youtube here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ObWwKn2sAfk